“The Mysticism of Saint Ignatius of Antioch”

Brother Ignatius Schweitzer, OP

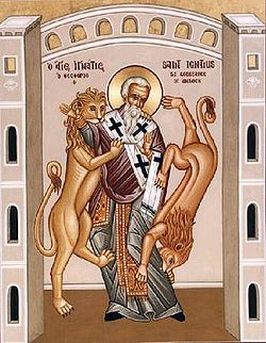

Saint Ignatius of Antioch (d. ca. 117) is perhaps best known for his courageous witness to the Catholic Faith. This was a witness of both word and deed. With persuasive words in his letters, Ignatius defended Christ’s divinity, Christ’s humanity (against the Docetists), the Eucharist as the true flesh and blood of Christ, the God-given authority of the bishop, and the necessity of the visible unity of the Church. This witness of words, however, reached its culmination in a heroic deed. As he wrote his seven letters, Ignatius was traveling the road to martyrdom. As the bishop of Antioch he had been arrested for the Faith and was being escorted to Rome to be fed to the lions. Although Ignatius is most often thought of as apologist, martyr, and bishop, in this essay I wish to consider him as mystic. First, I will justify attributing to him the term “mystic.” Then I will consider three aspects of Ignatius’ mystical relationship with Jesus along with their three corresponding fruits: Christ’s dwelling within, participation in Christ’s redemptive sacrifice, and imitation of the mystery of God’s silent deeds flowered in his work as apologist, martyr, and pastor, respectively. Besides filling out the account of his life, this spiritual approach gets more to the heart of the matter. For where else did Ignatius receive insight in his defense of the Faith if not from his interior dialogue with He who is the Truth? Where else did he receive the passionate zeal to face even the lions if not from his Master who endured the Cross for the sake of the world? And where else did he receive the solicitude to guide his flock as an exemplary pastor if not from being carried upon the breast of the Good Shepherd where he learned the silent mysteries of God’s heart?

Ignatius as Mystic

To claim that Ignatius is a mystic, I must first be clear what I mean by the rather ambiguous term “mysticism.” For my purposes here, I will adopt a succinct definition given by Evelyn Underhill in her classic study Mysticism: “the art of establishing [one’s] conscious relation with the Absolute.” Since all Christians are in a relationship with God, the key distinguishing mark of the mystic is being more keenly conscious of various aspects of that relationship. The Christian mystic has greater insight into and appropriation of the mysteries all Christians share in to some degree. Furthermore, Underhill’s definition implies the active life-commitment essential to establishing a more intimate relation with God. This point will be stressed by Ignatius: it is truly becoming a disciple that matters and not what one may experience or say. For this reason, Ignatius refrains from speaking directly of the more spectacular aspects of his own mystical life. He says, “I have many deep thoughts in God, but I take my own measure, lest I perish by boasting….For I myself, though I am in chains and can comprehend heavenly things, the ranks of the angels and the hierarchy of principalities, things visible and invisible, for all this I am not yet a disciple” (Tra 4:1, 5:2). Ignatius’ mysticism is characterized by “sober inebriation.” He keeps in proper perspective inessential things while articulating profoundly three essential features of a spirituality of true Christian discipleship: Christ’s indwelling, participation in the Cross, and deeds of silence.

Christ’s Indwelling

Ignatius’ spirituality in general and his defense of the Faith in particular are anchored in the presence of Christ dwelling within him. In referring to the mysteries of Christ he notes that he hopes the Lord will reveal more to him (Eph 20:2, cf Pol 2:2). He depends on some sort of mystical communication from the Lord for deeper insight. That the Lord Jesus teaches him in interior dialogue is so central for him that at the beginning of every letter Ignatius identifies himself as “Theophorus,” meaning both “God-bearer” and “God-inspired.” The latter flows from the former; inspiration or insight into the Faith depends on bearing God within in continual interior communion. And so Ignatius encourages the Church of Ephesus to “do everything with the knowledge that he dwells in us, in order that we may be his temples, and he may be in us as our God—as, in fact, he really is” (15:3). Ignatius encourages what is often called the practice of the presence of God. That Christ dwells within every baptized believer, who is in a state of grace, is a reality whether or not the given Christian is aware of it. Yet it is the frequent and even habitual recognition of this reality that results in growing intimacy with Christ and immersion into his mysteries. Such continual communion or constant prayer imbues every activity with a new quality of life and opens the Christian to God’s guidance. Ignatius wrote of the “living water in me, which speaks and says inside me, ‘Come to the Father.’” (Rom 7:2) This communion with Christ is what gave Ignatius the desire and strength to face the lions in martyrdom. He writes to the Smyrnaeans, “‘with the beasts’ means ‘with God.’ Only let it be in the name of Jesus Christ, that I may suffer together with him! I endure everything because he himself, who is perfect man, empowers me” (4:2).

Such profound communion based on continual prayer is no easy endeavor. However, there are two aids to this practice to which Ignatius alludes. First, frequent reception of the Eucharist, Jesus’ substantial presence, renews and invigorates Jesus’ constant spiritual presence within. As such, Ignatius encourages the Ephesians to “abide in Christ Jesus physically and spiritually” (10:3) The physical Eucharist ensures the spiritual communion that can be recalled throughout the day. Second, simply praying the name of Jesus throughout the day can be a consistent reminder triggering a keen awareness of his presence within one’s heart. A legend concerning Ignatius arose by the Middle Ages that perhaps reveals how committed he was to the invocation of the Name. In the midst of being torn to pieces by the lions, Ignatius continued to cry out, “Jesus!” Onlookers asked why he kept doing this. Ignatius replied that “Jesus” was inscribed in his heart. After his death, the executioners cut open his heart and looking within found inscribed in gold everywhere: “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus…”

Redemptive Sacrifice

The fact that Ignatius willingly faced and even desired martyrdom reveals that his spirituality was marked by the notion of sacrificial offering. Ignatius sees his sacrifice as united to Christ’s offering on Calvary and hence participating in the Cross’ redemptive efficacy. Jesus’ Passion bore sufficient fruit for the redemption of the whole world, yet in raising Christians to the dignity of sons who are privileged to share in his work, the Father has given them a share in applying these fruits toward themselves and the salvation of others. This participation in Christ’s sacrifice is wholly by grace and is itself a fruit of the Passion so that there remains an infinite gulf between the work of Christ and those who share in it.

Ignatius uses a rich image to express the reality of the Body of Christ sharing in the redemptive sacrifice of its Head. Hearkening to the Vine and the Branches, Ignatius proposes the tree of the cross and its branches. He considers those who are planted by the Father as “branches of the cross, and their fruit [as] imperishable—the same cross by which he, through his suffering, calls you who are his members” (Tra 11:2) Not only can we bear fruit in others’ lives by our material assistance, evangelism, and prayers, but our sufferings can also be offered in union with Christ for the sake of others. Ignatius writes to the Ephesians, “I am a humble sacrifice for you and I dedicate myself to you Ephesians” (8:1).

It seems to me, that, once again, central to Ignatius’ understanding of redemptive sacrifice is the celebration of the Eucharist, which is not only a communion but also a sacrificial offering. He implores the Church of Rome: “Grant me nothing more than to be poured out as an offering to God while there is still an altar ready, so that in love you may form a chorus and sing to the Father in Jesus Christ” (2:2). The reference to the altar and singing chorus seems like a conscious allusion to the Mass. The Mass is the primary means by which the Christian is able to unite his own sacrifice to the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary since it is truly made present on the altar under the appearance of bread and wine. In referring to his martyrdom in terms that echo the offering of the Mass, Ignatius encourages the Church of Rome to see his death as such a sacrifice of praise to the Father in Jesus, that the only appropriate response is song.

Since spiritual fruit is not borne according to human discretion and calculation, but according to God’s will, the sacrifices that come inherently (and somewhat involuntarily) within one’s calling are generally more effective than the penances one may choose according to inclination. Jesus himself asked that the cup be removed if possible, but submitted himself to God’s will. It is within this context that we can understand why Ignatius so frequently refers to the virtue of gentleness. Gentleness in affliction reveals an acceptance of God’s will and the desire to respond with the love of Christ. Since one could rage against both a person and a situation, Ignatius considers gentleness as the Christian response to both fierce opponents (Eph 10:2) and trying situations (Tra 4:2). Gentleness surrenders in accepting the given circumstance, then proceeds to act according to the law of love. This is so essential for Ignatius that he claims that it is gentleness that destroys the ruler of this age (Tra 4:2). Was it not, after all, Christ’s gentleness as the meek lamb led to the slaughter that defeated the devil?

The Silent Deeds of God and Man

Ignatius’ exemplary service and example to his flock as pastor flowed from his own familiarity with God’s care for his people which culminates in deeds of silence. God the Father, the true “Bishop of all,” (Mag 3:1) is the model for all bishops. Ignatius praises the bishop of Philadelphia, Asia who “accomplishes more through silence than others do by talking” (Phi 1:1). Furthermore, Ignatius insists that “the more anyone observes that the bishop is silent, the more one should fear him. For everyone whom the Master of the house sends to manage his own house we must welcome as we would the one who sent him” (Eph 6:1). The bishop’s silence should be received as one would receive the Master’s own silence. What is it about this silence that is so valuable?

The general principle governing Ignatius’ notion of silence could be expressed in the contemporary slogan, “Actions speak louder than words.” For Ignatius, words have an illusory character while deeds really exist. He recognizes the tendency of fallen human nature to speak lofty words or to think more highly of oneself than is warranted. He realizes that he himself is not free from such a tendency. In his letters, Ignatius speaks of his desire for martyrdom, while at the same time not being entirely confident of his own words. Of course, as he is writing, he seems to be resolute in facing the lions, but how will he act when he feels them panting over him, their next meal? He often asks, will I prove to be a disciple in reality or just call myself one? Acts have real existence, words do not necessarily. Hence Ignatius claims, “It is better to be silent and to be, than to talk and not be” (Eph 15:1). Here Ignatius indicates the existential consequence of speaking or thinking illusory words of oneself. False words effect us on the level of being. Not of course that if one lies he will cease to exist, in nihilum, but rather one can diminish his existence as a Christian with such falsities. To fully exist in the Christian sense is to share in the fullness of life by being firmly rooted in one’s identity in Christ. Unlike the fleeting character of words, deeds done from this fullness of existence bear something of an everlasting quality. Ignatius, then, encourages his fellow bishop, Polycarp, to perform a charitable deed so “that [he, Polycarp] may be glorified by an eternal deed” (Pol 8:1). Deeds of love, even when done in the hiddenness of silence, have an everlasting effect.

This full Christian existence proved by deeds is in itself an essential witness to the Gospel and hence is the truest word a Christian can “speak”—albeit with whole his existence. As such, Ignatius’ high view of silence goes beyond being what one says he is, it also serves a revelatory role. Not only are deeds more substantial than words, they are also more revelatory; or rather, they are more revelatory by the very fact of the greater depth of being. So, Ignatius pleads with the Christians of Rome not to impede his approaching martyrdom, “for if you remain silent and leave me alone, I will be a word of God, but if you love my flesh, then I will again be a mere voice” (2:1). Though the spread of the Gospel demands vocal words, its ultimate attestation occurs in the silence of martyrdom. When the words of the Christian witness are snuffed out by persecutors, then the Word, himself, shines through brilliantly.

The fruitfulness of the martyr’s silence blossoms from the Word’s own silence. Ignatius notes, “The one who truly possesses the word of Jesus is also able to hear his silence, that he may be perfect, that he may act through what he says and be known through his silence” (Eph 15:2). As the revelation of the Father, the Word-made-flesh has more to say than can be expressed in words. In order to “hear” what is expressed in Jesus’ silence one must have the keen perception of faith. Only faith can discern God’s word of love in the apparent Godlessness of the Cross. Although Jesus does reveal the Father in his vocal preaching, his greatest message is proclaimed in the Cross’ silence. Actions do speak louder than words! Jesus himself, as Word, is the very message of God and his self-gift in silence gets at the heart of Revelation since it gets at the heart of God. There are, Ignatius claims, “three mysteries to be loudly proclaimed, yet which were accomplished in the silence of God.” (19:1) These are events which are not flashy enough for the world’s taste and hence, in this sense, are hidden from the world’s eyes. They are Mary’s virginity, Jesus’ birth, and the Cross. In other words, God’s preparation and actualization of his mother, his taking on flesh, and his death on the Cross—all of which are hidden from the world in the silence of God—are all crucial actions for God’s redemption of the world. The “one God who revealed himself through Jesus Christ his Son, who is his Word which came forth from silence,” (Mag 8:2) has given silent deeds a particular fruitfulness. Ignatius, then, in the silence of his martyrdom echoes the silence of God. He most effectively bears witness to the ultimate Love that knows no limit and shares in its fecundity for the sake of others. In this he fulfills his task as pastor in imitation of the Chief Shepherd who laid down his life for this sheep. Martyrdom is the epitome of the silent deeds Ignatius extols in his fellow bishops and encourages in all Christians. However, all acts of love—even when hidden from others—can be fruitful for others because they share in God’s own silent deeds of redemption.

The mysticism of Saint Ignatius of Antioch bore fruit in the concrete deeds of his life: communion with the indwelling Christ flowered in his insight as an apologist, participation in Christ’s Passion in his zeal as a martyr, and imitation of God’s deeds of silence in his exemplarity as a pastor. This spirituality sustained Ignatius to the end. So that when the Roman populace gathered for a thrilling show in the Coliseum, among the many other spectacles, they saw an odd figure embrace the lions as a man might embrace his beloved at a ballroom dance. Amidst the movement to and fro and the twirling of body parts—the graceful choreography of Nature consuming its prey—all that could be heard was the name, “Jesus!” None of the rabble noticed the man’s blood soaking silently into the earth, the seed of the Church.